Nurturing Hearts Before Grades: Japan’s Unique Approach to Early Schooling

In many countries, the moment children enter primary school, they face tests, drills, and pressure to perform. In Japan, however, the first few years of elementary education follow a very different philosophy. Rather than focusing immediately on exams or intense academic content, Japanese schools devote those formative years to character building, cooperation, and social responsibility.

A Gentle Start: Emphasis on Morality and Social Skills

Rather than diving straight into rigorous assessments, Japanese elementary schools typically delay formal nationwide exams until the fourth grade (around age 10). During the first three years, teachers prioritize cultivating traits like kindness, respect, responsibility, and the capacity to work with others. This period is designed to help students grow into well-rounded thinkers, not just high-performing test-takers.

Children engage in daily routines that teach them about teamwork and community: they clean their classroom, take turns in responsibilities like serving meals or organizing materials, and learn to cooperate in group tasks. These practices may seem humble — picking up trash, wiping floors, organizing desks — but they reinforce the idea that every member belongs to a shared effort.

Teamwork, Order, and the “Wa” Philosophy

A key cultural underpinning is the idea of wa — harmony or social cohesion. Japanese education views harmony not as passivity, but as an intentional balance of individual needs with group well-being. Students learn early to care for their surroundings and for each other. Classroom rules, quiet rituals, and communal chores reinforce the notion that a harmonious group is built by everyone’s small contributions.

In lessons and free activities alike, children often work in pairs or small groups. Whether solving a project together or cleaning the hallway, they learn to listen, negotiate, and respect others’ perspectives. This cooperative framework teaches emotional literacy and prepares them for future academic and social challenges.

Delaying Exams to Foster Confidence

By postponing high-stakes testing, Japan gives students time to adjust without the stress of constant evaluation. This approach encourages curiosity and intrinsic motivation over rote memorization or performance anxiety. As students grow stronger in social skills and confidence, they approach formal testing in later grades with a more stable foundation.

This system does not mean academics are ignored — core subjects such as reading, writing, and math are gradually introduced. But they are paced in a way that respects the child’s developmental stage.

The Shadow Side: Exam Pressure and “Exam Hell”

Of course, the Japanese system is not without its challenges. As students advance, pressure from high-stakes entrance exams looms large. From late elementary through middle and high school, some students enter intense preparatory cycles known colloquially as “exam hell,” where performance expectations intensify dramatically. Many families use after-school cram schools (juku) to bolster exam readiness.

This contrast — a calm, character-based early schooling environment followed by rising academic pressure — is a tension critics of the system often point out. Students who once learned to love school may later feel burdened by competition and expectations.

Building Better Citizens — Beyond Test Scores

Despite its challenges, Japan’s early education model offers something rare: a place where character and community come before grades. By teaching children to care for their environment, respect others, and collaborate from the start, the system aims to create citizens who value balance as much as achievement.

For nations debating education reform, Japan’s approach raises interesting lessons: that skills like empathy, responsibility, and social cohesion may matter just as much as academic knowledge — especially when introduced early.

News in the same category

Saudi Arabia Announces Major Gold Discovery Near Mecca, Boosting Mining Ambitions

Rare Wondiwoi Tree Kangaroo Seen Again After Nearly a Century

3 types of shirts you should never wear to a funeral

31-Year-Old Man Invited 89-Year-Old Neighbor To Live With Him To Spend Her Last Days In Company

Saudi Arabia Announces Major Gold Discovery in Makkah Region — A Potential New Mining Belt

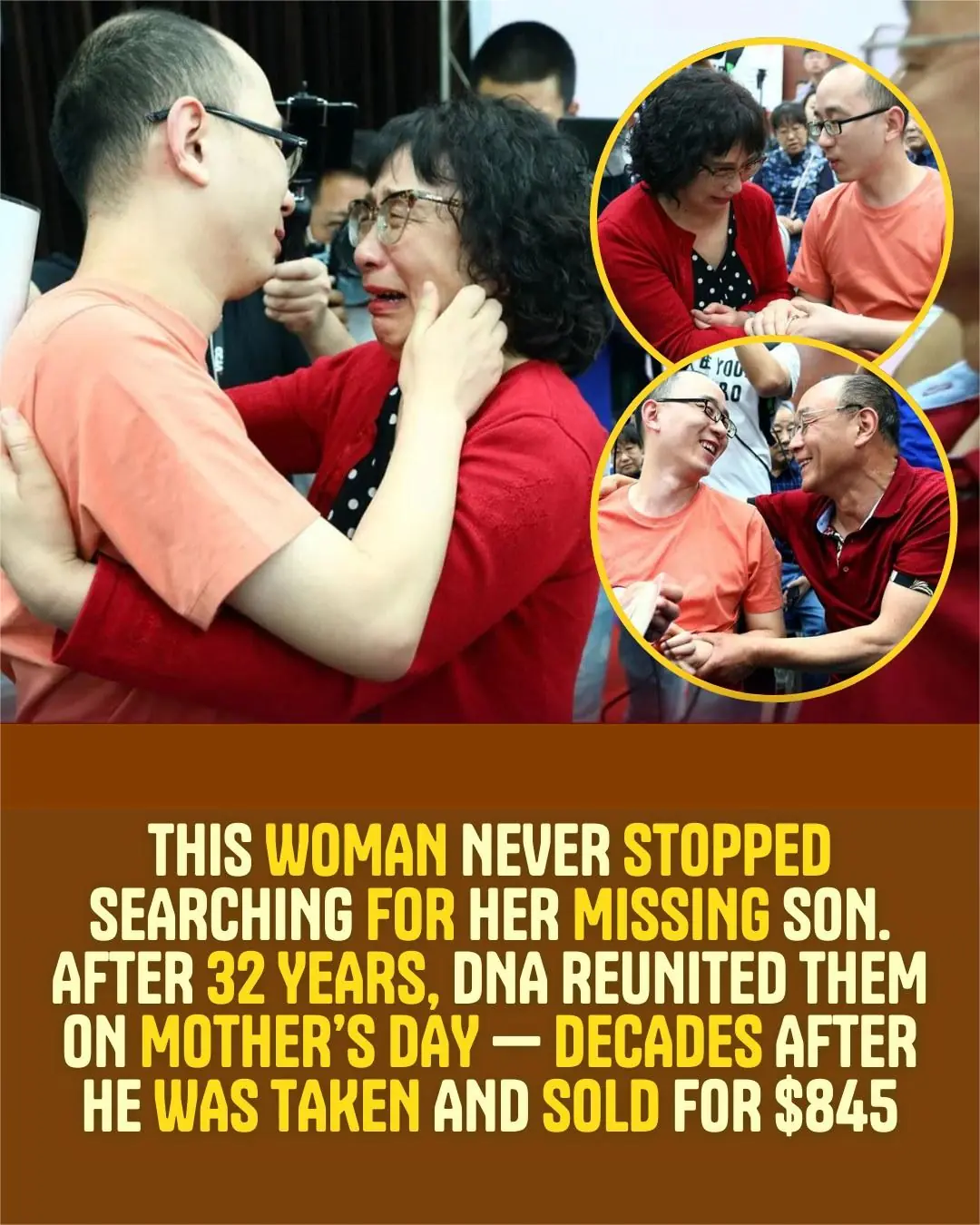

After 32 Years, Chinese Mother Reunites With Son Kidnapped and Sold as a Toddler

Taylor Swift’s Quiet Act of Kindness: Helping a Pregnant, Homeless Fan Find Stability

Raging anti-ICE protester forgets to put car in park, watches it sink into lake while yelling at agent arresting illegal alien

Babies Who Wake Up Often at Night Might Be Smarter, Expert Suggests

Flight Attendant Reveals the Real Reason Cabin Crew Greet You When You Board — and It’s Not Just Politeness

Mike the Headless Chicken: The Incredible Survival Story That Defied Biology

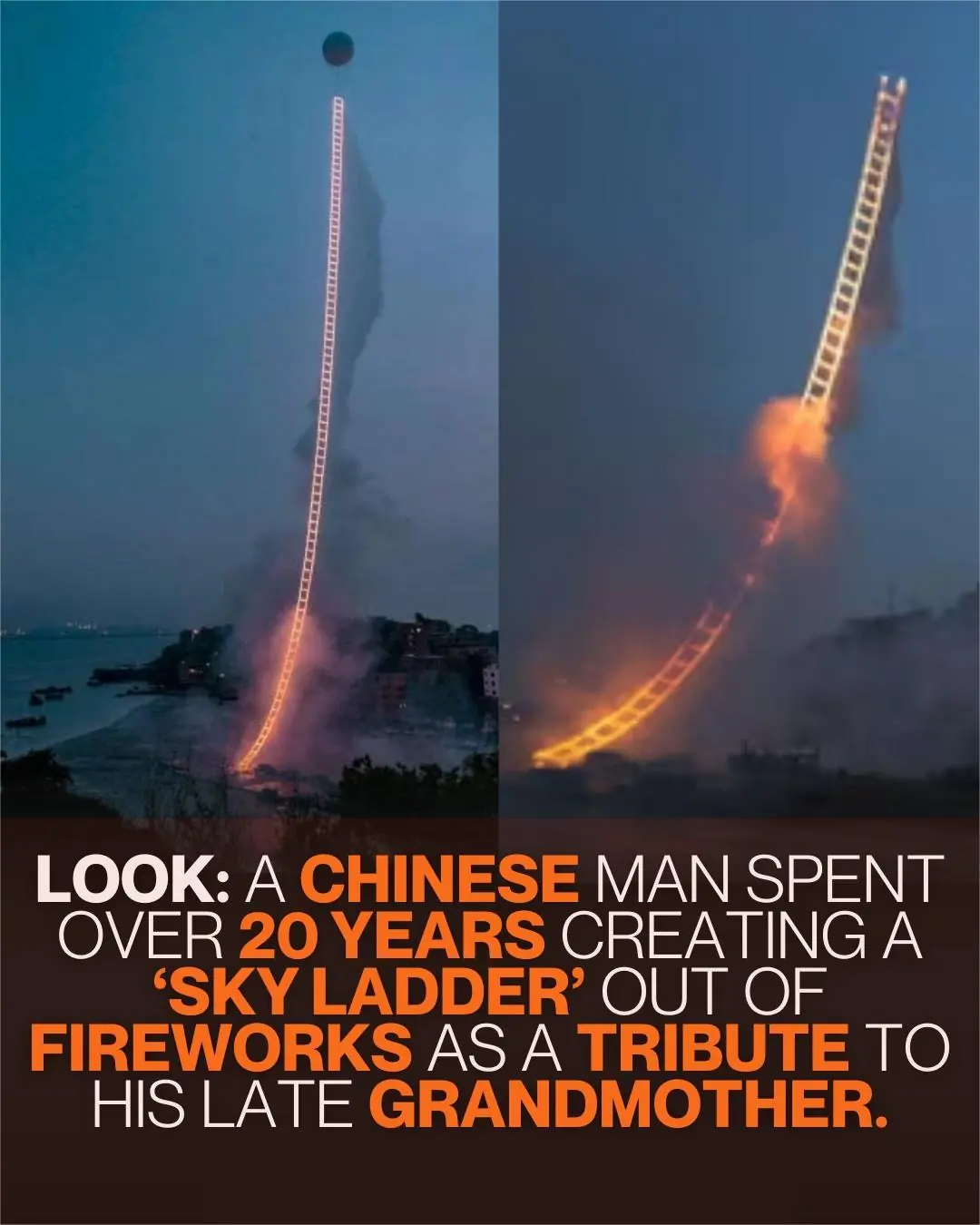

Chinese Artist Cai Guo-Qiang Realizes 21-Year Dream With Dazzling ‘Sky Ladder’

New iguanodontian dinosaur discovered in Portugal

Tina Turner statue unveiled in Tennessee community where she grew up

Sea Otters: The Ocean’s Clever Tool-Users With a Pocket Full of Rocks

Dolphins’ Underwater Bubble Rings Reveal Remarkable Intelligence and Playfulness

Ozone Layer on Track for Full Recovery by 2050: A Triumph of Global Cooperation

News Post

Unlock Nature’s Secret: The Magic of Mango Leaf Tea with Cloves

Unlock Nature’s Secret: The Magic of Mango Leaf Tea with Cloves

Got a Sore Throat? Try This Tiny Spice That Works Like Nature’s Antibiotic

The Morning Elixir You’ll Wish You Discovered Sooner: Unleash a Hidden Energy Surge with the Banana-Coffee Blend

Powerful Natural Blend for Men Over 40: Regain Your Strength and Vitality

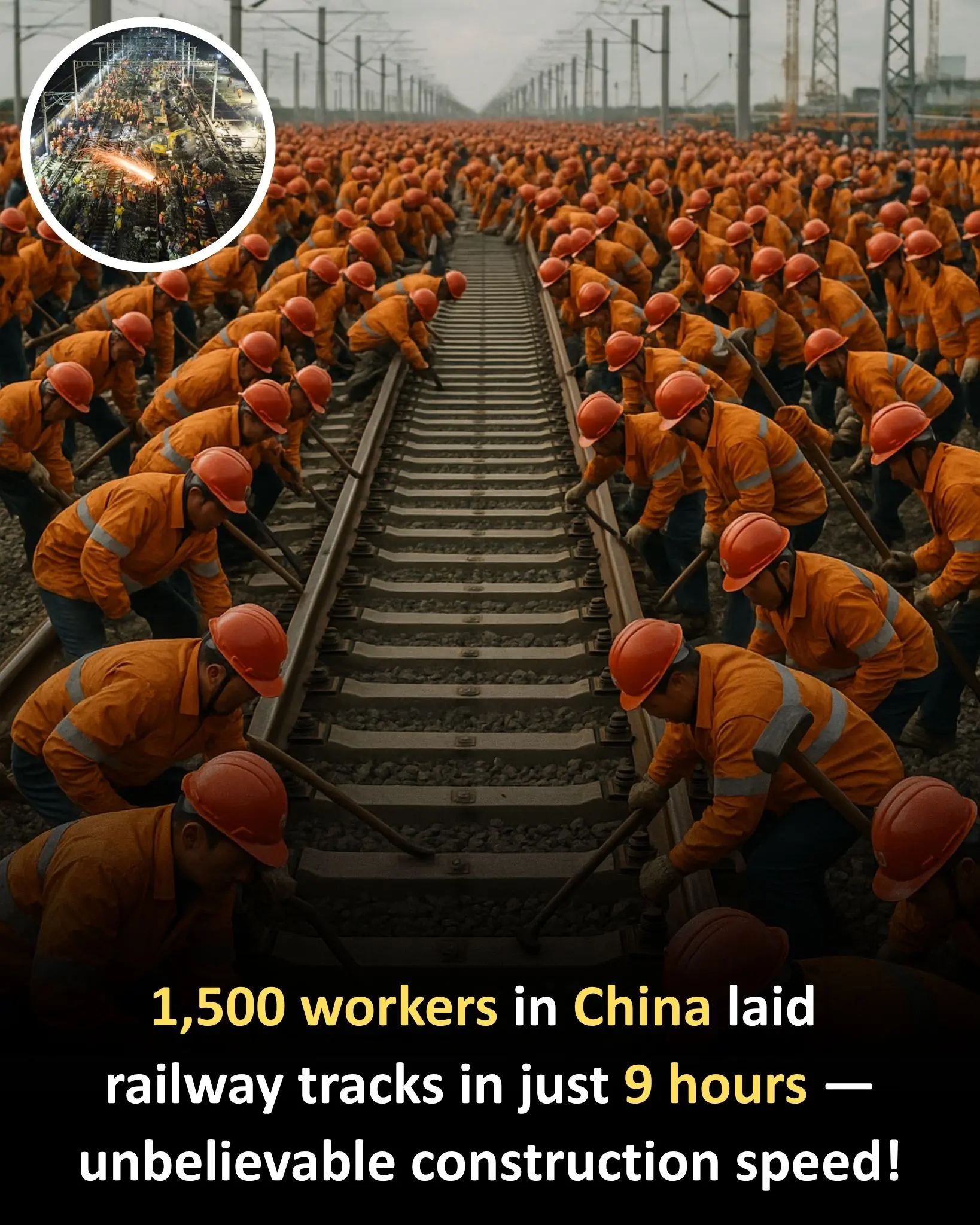

China’s Remarkable Railway Feat: 1,500 Workers Complete Complex Track Project in Just Nine Hours

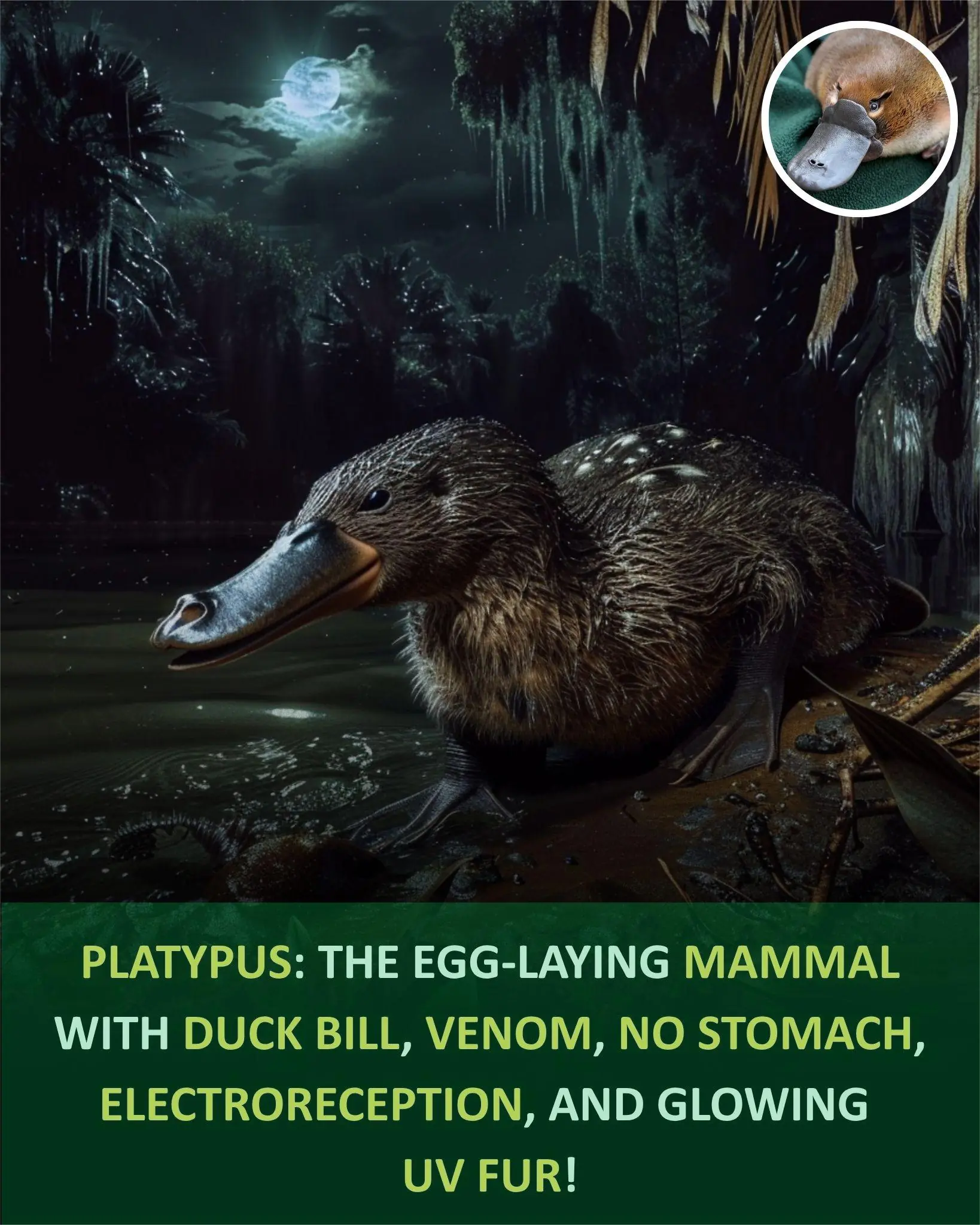

The Platypus: One of Nature’s Strangest and Most Fascinating Mammals

Saudi Arabia Announces Major Gold Discovery Near Mecca, Boosting Mining Ambitions

Rare Wondiwoi Tree Kangaroo Seen Again After Nearly a Century

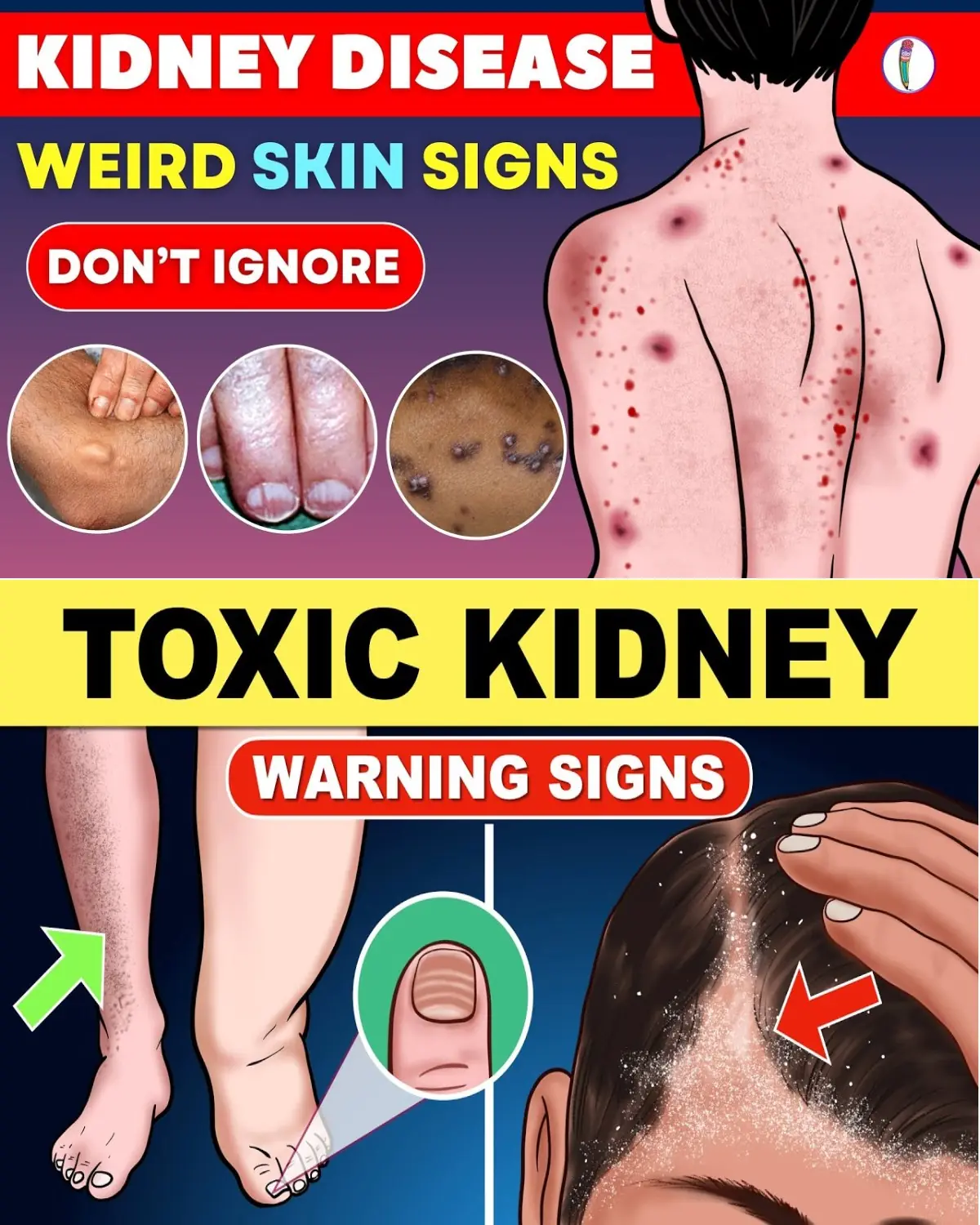

Skin Signs of Kidney Disease: What Your Body Is Telling You

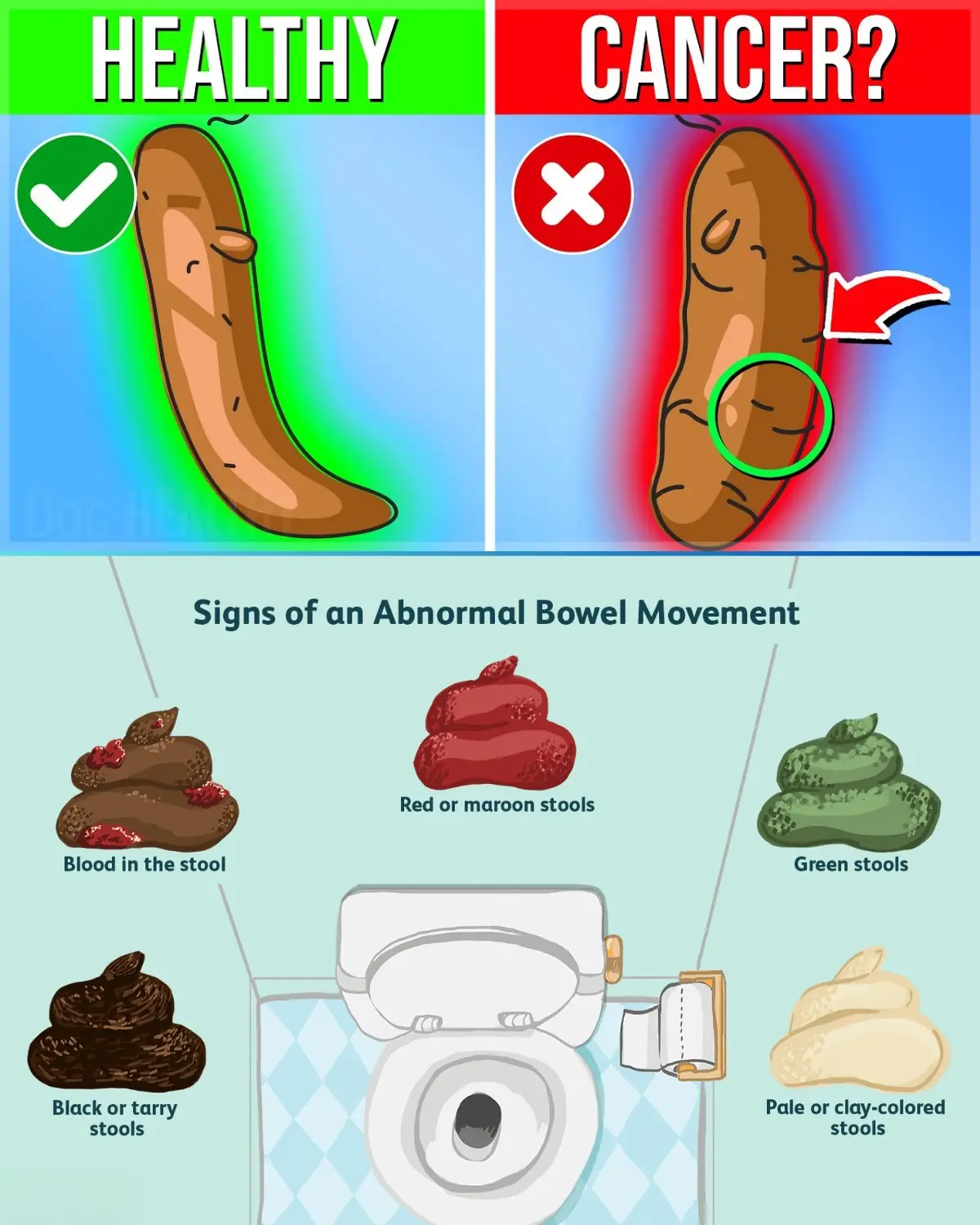

What Your Stool Color Reveals About Your Health

Brown Sugar Pecan Bundt Cake

Avocados: The nutrient-packed fruit doctors recommend

Flaxseed Baby Oil Formula: Collagen Oil For Wrinkle Free Skin

3 types of shirts you should never wear to a funeral

Unveil Colgate’s Surprising Secret for Softer Feet

Little boy cries at gate—k9 dog senses something no one else does

The reason dogs often chase people